An annual celebration observed in various parts of East Asia, especially China, is the Dragon Boat Festival, sometimes called the Duan wu Jie Festival. With its deep cultural importance, this lively event is known for its dragon boat racing and zongzi (sticky rice dumplings) consumption. The question of whether the Dragon Boat Festival legend is true lingers, nevertheless, and many are curious about it. Investigating the beginnings and folklore around this venerable custom can help us to find the answer.

The Legend of Qu Yuan

The most commonly recognized legend surrounding the Dragon Boat Festival centers on Qu Yuan, an ancient Chinese minister and patriotic poet who lived during the Warring States period. Qu Yuan was a Chu State official who was banished as a result of corruption and political scheming. On the fifth day of the fifth lunar month, Qu Yuan is reported to have drowned himself in the Miluo River, having witnessed corruption and been very upset by the situation of his nation.

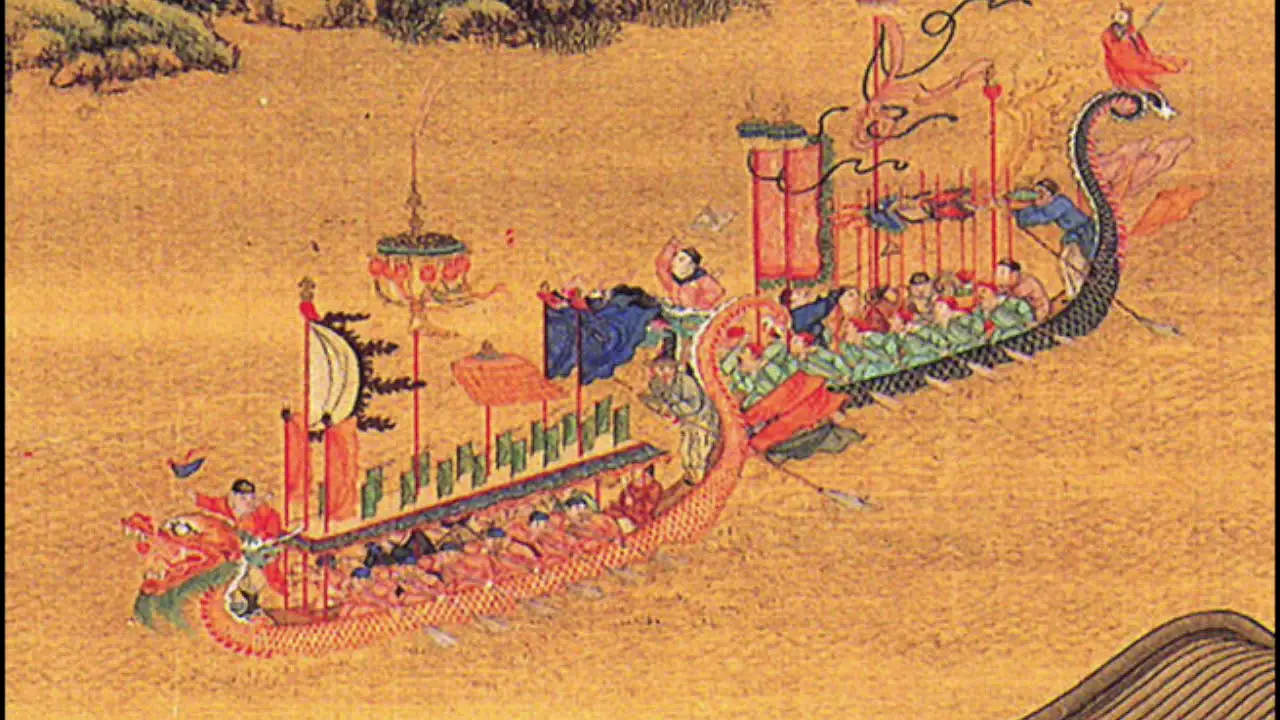

The locals, who revered and esteemed Qu Yuan, are said to have hurried out on their boats to save him or at the very least retrieve his body. To frighten away fish and bad spirits, they pounded drums and sprayed the water with their paddles. To deter the fish from devouring Qu Yuan’s corpse, they also dumped rice into the river. Dragon boat racing and the custom of eating zongzi during the festival are thought to have originated from this act of sadness and remembrance.

Historical Evidence and Cultural Significance

Historical Context

Though there is a lot of factual evidence to corroborate the specifics of Qu Yuan’s life and death, the story is profoundly embedded in the festival’s tradition. As a statesman and poet, Qu Yuan was a real historical character most recognized for his thought-provoking pieces such as “Li Sao” (“The Lament”). He has a long history of state devotion and significant contributions to Chinese literature.

What is harder to confirm are the precise circumstances surrounding his passing and the locals’ subsequent conduct. Historical and legendary aspects frequently overlap throughout ancient Chinese history, making it challenging to distinguish between the two completely.

Cultural Evolution

Over thousands of years, the Dragon Boat Festival has changed, absorbing many regional variations and customs. The festival’s rich tapestry is enriched by additional legends, among which Qu Yuan’s story is the most well-known. For example, some areas venerate Wu Zixu, another historical figure, while other areas might honor other local heroes or deities.

The festival’s capacity to communicate cultural values like patriotism, communal pride, and reverence for ancestors accounts for part of its ongoing appeal. These fundamental principles are reflected in the festival’s customs and activities, which include racing dragon boats, preparing and consuming zongzi, and hanging calamus and mugwort.

The Real Story: A Blend of Fact and Myth

The Dragon Boat Festival: is this a true story? In both cases, the answer is no. Qu Yuan, a genuine person whose life and accomplishments have had a lasting influence on Chinese culture, and historical events are the festival’s beginnings. However, throughout ages, mythological aspects have probably been added to the precise account of his death and the customs that followed.

Stories in many cultures are evolving to reflect deeper meanings and ideals, and this merging of mythology and history is a typical process. The communal memory and cultural identity that the story reflects, rather than the actual reality of a particular story, are the true focus of the Dragon Boat Festival.

FOR MORE LATEST AND INTERESTING BLOGS PLEASE VISIT OUR PAGE = https://usabloghouse.com/blog/

Conclusion

Chinese cultural legacy is fascinatingly revealed through the story of the Dragon Boat Festival, which combines historical details with legendary embellishments. Even though there is still much mystery surrounding Qu Yuan’s life and death, the festival is nevertheless a lively and significant occasion to celebrate. Through common customs and ideals, it respects the spirit of community, patriotism, and resiliency while bridging the gap between myth and reality.

The capacity of the Dragon Boat Festival to unite people in celebration of their shared cultural heritage and sense of collective identity, rather than the historical veracity of its founding tale, is ultimately what gives it its true core.